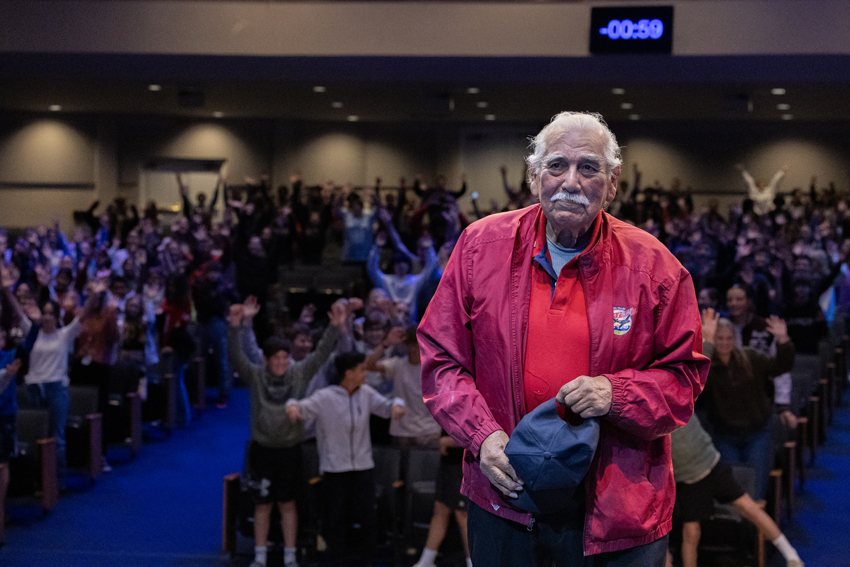

This is one of three installments featuring the veterans of World War II in prologue to the Veterans Day Parade, in Downtown Fresno. This features first hand experiences through the eyes of veteran Norris Jernigan, the effects of World War II.

For the previous installment, read the Oct. 22 article, Veterans Commemorated by Central Valley Honor Flight.

The Feather encourages readers to honor, cherish and protect the stories of our veterans and their accounts of our miraculous history as a country.

On a sunny morning in December 353 Japanese fighter planes flew over the big island in Hawaii and destroyed most of the U.S. naval fleet, the event now know as Pearl Harbor. These actions spurred the deployment of nearly 16 million young men to the European and Pacific fronts.

It is estimated that 555 World War II veterans die everyday, less than a million out of the original 16 million veterans are still alive today. Consequently, the stories and experiences of countless veterans have been lost to the force of time.

At the time a young man, Norris Jernigan, learned firsthand what was, and still is required of a United States army soldier. Dependability, courage, decisiveness and effort were key traits that enabled Jernigan to assist the Enola Gay and the 509th Composite Group in completing their highly secretive mission of the Enola Gay.

Without being involved in the mission, a person could not possibly understand the magnitude of work and perfection that was required of Jernigan and his fellow soldiers. That is why he is extremely valuable to all of us that were not there.

Jernigan is a true patriot and is full of information that can help all of us understand our counties history on a deeper level.

People today can not be educated about the history of our country without learning from people that participated in it. Controversy surrounds many events from WWII, but none as much as the use of the atomic bomb on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Fat Man and Little Boy were the first atomic bombs ever used in the context of war. The estimated death toll was over 230,000.

The Army Air Corps. unit assigned the task of carrying out the bombing of the two Japanese cities was the 509th Composite Group. Among the 1,700 men in the 509th, one man, Norris Jernigan, has survived 70 years to share his experiences in the Pacific.

Born in Eugene, Oregon, in 1925, Jernigan and his brother were raised by the their widower father, an employee of the Southern Pacific Railroad. His childhood home is still standing and has since been commandeered by a law firm for their law office.

When Jernigan was a junior in high school, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps., which we know now as the Air Force, following suit of his brother. He enrolled in the cadet program in hopes of becoming a pilot.

On August 13, 1943, Jernigan reported for duty at the Oakland pier to board a Shepherd field, Texas-bound group train. It was there that Jernigan received his basic training.

“Growing up on the farm made me pretty rugged,” Jernigan said. “I got by basic training a lot better the most of the other men. I was pretty conditioned from working in the heat all day.”

After his one month of basic training, he was sent to complete one semester at Denver University, the school where he underwent his first pilot training. After his training in Denver Jernigan was sent to Santa Ana military base to await his new assignment.

Jernigan spent most of his early military career on different bases doing whatever job he was assigned. In 1944 he was reassigned once again to the squadron intelligence office in Fairmont, Nebraska. On the job training, in Nebraska prepared Jernigan for important work in Wendover, Utah.

The 393rd bomb squadron was sent to Wendover to become part of the 509th composite group. The group consisted of all factions necessary to have a self sufficient group.

“When we arrived in Wendover we met lieutenant colonel Paul Tibbits,” Jernigan said. “He told us that we would be the bomb squadron involved in a highly secret project that if successful would shorten the war by two years.”

The project that Col. Tibbits was referencing, now known as the nuclear bomb. Not every soldier was right for the job of protecting such a powerful weapon, or merely the information of it’s existence.

(PODCAST) Norris Jernigan, 509th Composite Group–Nov. 10, 2014

Some of the original members of the 509th composite group were deemed as unfit by their superior officers to keep the confidentiality of the mission. The town of Wendover had many plants in it tom watch and listen to the recruits and see if they were cut out for the job.

After the groups briefing in Wendover they were sent to the recently liberated island of Tinian. Tinian lies off of the coast of Guam and was fabricated for the 509ths specific needs.

Four B29 runways were constructed from natural resources found on the island such as coral rock. Tinians north air field would serve as the central location for Jernigan’s mission.

“The natives of Tinian were a primitive group of people at the time,” Jernigan said. “But they never caused any trouble with us.”

Originally, Fat Man and Little Boy were to be simultaneously dropped on Japan and Germany. When the European front closed the bomb intended for Germany was freed up for use in the Pacific.

Three bombs were constructed for use against Japan. The target cities were Hiroshima, Kokura and Nagasaki. The third bomb was only to be used if the Japanese refused to surrender.

“At first, the second bomb was to be used on Kokura,” Jernigan said. “Due to overcast weather though, the pilots could not bomb by sight and sighted to move to the next target, Nagasaki. While over Nagasaki, the bomber used a T-shaped bridge in the city as a reference point to drop the bomb.”

The bombs, both weighing around 10,000 pounds, never actually hit the ground, but instead were detonated 2,000 feet above the ground, to inflict the most damage.

Due to immediate and lasting effects of the bombs, there is no count of exactly how many casualties.

Jernigan’s mission was successful in shortenings the war by two years and saving countless Japanese and American lives.

“Had we not bombed Japan, the war would have continued for at

least two more years,” Jernigan said. “The Japanese have an almost fanatic loyalty to their Emperor and would have fought to the death for him. By completing our mission, Japan realized the power of America and rightfully surrendered.”

Controversy surrounds the bombings of Japan and some Americans are still critical of of the mission. Modern school textbooks lack complete details of other possible outcomes that would have cost more lives from both countries.

“If I was put in that same situation with what I know now,” Jernigan said. “I would still complete my mission to the best of my ability and I believe the deceased men in my group would say the same. It had to be done for the good of both nations.”

Of the original 1700 members of the Enola Gay group, only seven are still alive today. The stories and true information of the mission, one of the greatest military displays in the history of the world, are being slowly lost.

Jernigan recently attended the fifth Central Valley Honor Flight, Oct. 27-29th.

“The trip was amazing and very meaningful,” Jernigan said. “The names on all of the walls hit me very hard this time, just to think about all of those men losing their lives to protect our country.”

The Feather would like to thank Norris Jernigan for your service and thank all of our veterans past and present for your unwavering protection and determination to keep our great nation safe.

For more information on Jernigan and other veterans, check out Hometown Heroes, hosted by Paul Loeffler on KMJ at 12 p.m.

Follow The Feather via Twitter @thefeather and Instagram @thefeatheronline. The writers can be reached via twitter @namoodnhoj and @beal2015.