Serena Zhao explores Chinese and America’s First Amendment rights during Scholastic Journalism Week

As a Chinese international student, feeling enriched by hearing so many voices, I understood that I know so little about the world before I entered the U.S.

While the First Amendment guarantees freedom concerning religion, expression, assembly, and the right to petition, The Constitutional Law of the People’s Republic of China indicates the same meaning as the First Amendments in the U.S in article 35.

According to Article 35, “Citizens of the People’s Republic of China enjoy the freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession, and of demonstration.”

Personally, this statement exists like a mirage for me. In China, we can’t just go on the streets to protest unless the leaders report, and it is then approved by a local governance institution.

Terry Cui is a senior broadcast journalist who worked in a TV station in China for 10 years and now serves as a Fellow for Hubert H. Humphrey Fellowship in Phoenix, U.S.A.

“In our (Chinese) constitution, it really had some words about freedom of speech, but the reality is totally different,” Cui said. “To be a journalist in China, we work in the censorship system. The censorship system means that our leader is censoring your topic before you interview or report.”

Cui currently works as a professor at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

Indeed, Chinese students don’t have events like Scholastic Journalism Week to highlight the hard work of student journalists across the nation.

With the Scholastic Journalism Week (SJW) theme “Big Questions, Big Results,” Journalism Education Association (JEA) and Student Press Law Center (SPLC) work together to celebrate student journalists who seek out essential questions about the world around them and convey robust reporting to inform and thoughtfully benefit the audience.

SJW’s theme is to encourage students to investigate the stories, trends, and issues to deepen their understanding of the community and cover the publications in real time.

However, from a Communist perspective, it is common for the public in China to follow the government and our president without thinking or speaking intense opinions. It is not because we are scared of the government, we feel there is no need to investigate and express since everybody is on the same boat.

Cui thinks some positive effects would be that journalism easily unites citizens in China together.

“They can follow the government’s leading voice from our leaders,” Cui said. “Our media has a lot of propaganda to encourage people to work hard, to follow proper moral regulation, and to believe in our country.”

When I was back in China, I wouldn’t be interested in political topics. Rather than in the United States, which has multiple political parties, the root of Communism under one system in China is stable and unified.

However, instead of going with the public stream in China and mute at many controversial issues, I think it’s more important to pay attention to the world and think independently and discuss the ramifications of different events or issues.

Yet, I believe everyone has a right to share their stories and questions they saw or encountered. If we lose the ability to investigate, recognize, and critical thinking, we will also lose the ability to act quickly before an emergency and crucial issues.

Fascinated by the concept of freedom of expression, I took a summer course “Free Expression and Community Engagement: Principles and practice of civic discourse” at the University of Chicago, July 2019.

In a classroom seminar setting, we talked about community issues, social media, and political trends that I wouldn’t be able to speak of in China.

Individually, we were required to conduct research and suggest solutions for a critical question or issue within our community.

Looking at my classmates brainstorming ideas to present to school boards, community leaders, and even mayors, I didn’t know what to do because I knew no one would listen to an individual civilian who was trying to think differently and change a whole food delivery system that the government had been established for them.

One of the main focuses of Scholastic Journalism Week is #Press4Education. The Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) and JEA are looking to match journalists and K-12 teachers in a nationwide effort to bring more journalism education to schools.

The project provides lesson plans, presentations, and other resources to journalists who want to volunteer to share their knowledge. Besides, SPJ provided topics for making presentations, including ethics, social media, and online reporting.

The SPJ establishes its preamble to “ensure the free exchange of information that is accurate, fair, and thorough.” They are dedicated to protecting the First Amendment right of Freedom of Speech and press for journalists while stimulating ethical behavior.

As an international student journalist studying abroad from China, I think journalism education is necessary worldwide, no matter what function of government countries have. We need to provide a voice for the voiceless about questions and conflicts in local, state and national issues. However, it is hard to input some ideas of freedom of speech and press for everyone in a Communist country.

From Cui’s perspective, the journalism field in China is an integral part of a Communist country system. Therefore, the government attaches importance to journalism education for teenagers.

“But when they actually go on the path of journalism, the first thing they should learn is to follow the party and the system,” Cui mentions. He thinks this is the significant difference between journalism students in China and the United States.

In the following podcast, Serena Zhao, ’20, talks to Terry Cui about the importance of journalism education and how he views journalism in China.

Following the tragically outbreak of coronavirus in China, the public panicked by witnessing the news. According to Los Angeles Daily News, the whistleblower, Dr. Li Wenliang, has passed away due to infection.

But it was all too late because nobody listened and trusted the questions that he found and was hoping to resolve by revealing to the society.

In late December of 2019, Dr. Li typed in his group chat, suspecting possible SARS infection of several patients and remind other doctors to be careful. As the fear goes around the hospital, Dr. Li was reprimanded by local police for “spreading rumors” about the illness in late December.

As a doctor, all he did was try to inform the public and take action when the government did not. He sought out an important issue but was not allowed to quickly educate the public.

Before getting severely infected by coronavirus, Dr. Li said, “a healthy society should have more than ‘one voice’ in an interview.”

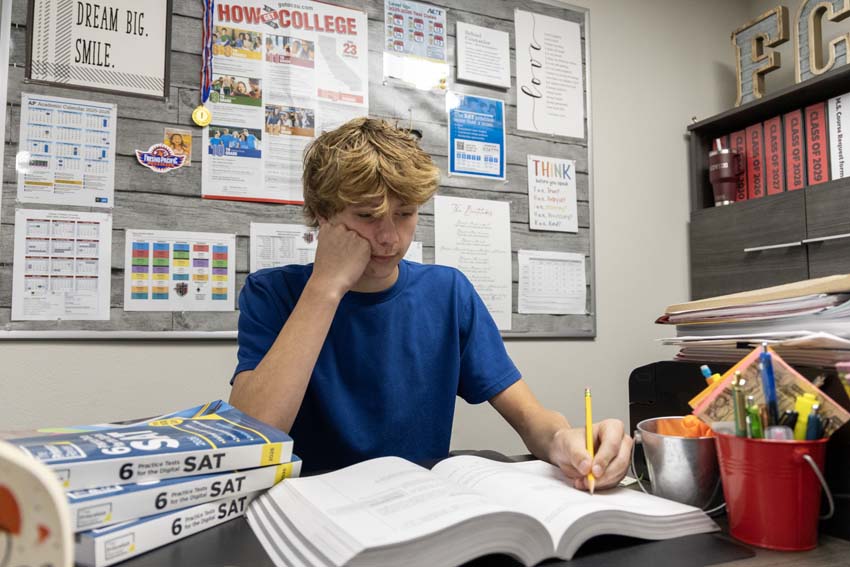

Over the years, The Feather staff has interviewed many national media leaders, including EdSource.org senior editor Denise Zapata during the Roger Tatarian Symposium, Feb. 26. Junior Morgan Parker, is currently writing an article on the power of online journalism to be published next week.

One thing that completely blows my mind as being an international student from China is to see the comprehensive and in-depth coverage U.S journalism field has for the public. It is hard for me to wrap my mind around social media such as Twitter and Facebook the first time I came here.

Despite people having inside conversations about the government, laws, and regulations in China at their home, millions of people speak freely in social media in the U.S. about whether they like or dislike their government and even their President.

However, I think people in the U.S. may have the freedom to express opinions and learn and think for themselves, but at the cost of causing conflicts. When everyone is entitled to their opinion, it’s hard to get people to rally together and respect one another.

I never knew how important it is to immerse journalism education to people before I study abroad and joined The Feather Online. This step allows me to interview many professionals I choose, write about exciting topics, and express my thoughts under responsible and ethical behavior.

Even though I am an operator for an official account on the Chinese-based social media site WeChat, there are specific topics, such as politics and science, that we cannot write and publish online.

If I have to post something to voice out the views, we would need to watch over every word, sentence, and make sure the internet doesn’t detect us as “Politically sensitive,” which will then terminate the Official Account forever.

By taking ownership of my own education, I joined publications and became a student journalist. I encourage international students in the U.S to join publications in schools to widen our perspectives and learn journalism skills that will help you in life.

For more Feather articles, read COLUMN: Architecture focus drives service dreams, reflects social change, COLUMN: China-born senior reviews local Chinese food in Fresno area, and COLUMN: Global impact begins at local level.

luke Wu • Mar 5, 2020 at 8:04 am

Great article! Serena. Thank you for sharing your opinion!

Wesley Hinton • Mar 5, 2020 at 7:49 am

Great article Serena!! It was very interesting to hear a perspective from outside the U.S. on journalism. I loved reading about the differences between journalism and media in America and China.

Summer Foshee • Mar 5, 2020 at 7:23 am

Amazing article, Serena! Thank you for showing us how news and free speech works in China. Your writing was very thought-out and professional.

Natalie • Feb 28, 2020 at 8:38 pm

What a great way to own your education – investigate your own beliefs, compare and contrast with your current experiences, balance that with inquiry and expert opinion. Great job Serena!

Thy Pham-Nguyen • Feb 28, 2020 at 10:35 am

I love this article so much. Can’t stop reading it.

It is very powerful but also interesting. Well done Serena.

Sarah Upshaw • Feb 28, 2020 at 10:01 am

Wow these articles are amazing!!

Silva Emerian • Feb 27, 2020 at 11:59 am

Thanks for sharing your thoughts and perspective, Serena. You really highlighted the pros and cons of journalism in both countries. Keep up the great work!