Since the beginning of written history, books have dominated as the main source of knowledge for civilized society because of the information and sophistication they offer.

Books used to be so important to people that armies would burn down the libraries of the cities they conquered so as to wipe out the information that their combatants had accumulated over years of study and research. Even 70 years ago, with the fascist regimes like that of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany, the burning of books was seen as cleansing, or getting rid of “useless” information.

The same sort of purging can be seen in society today, not in the destruction of information but in the condensation of it. It would seem that the invention of modern machines such as the television, radio and computer have made long, drawn-out works a thing of the past, and labeled them as pointless or a waste of time. In the 21st century, books, and the written word in general, have begun to become obsolete, being replaced by faster, more advanced media and technologies.

Despite this circumstance, literature from any time is not simply a bygone artifact. It is a storehouse of direction and wisdom, which can be used by current and future generations alike. However, compared to more modern media, reading books is a time-consuming and sometimes difficult pastime.

That is the main reason services like SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, both websites that condense the details of novels, are used; they’re seemingly effortless. Instead of spending hours reading an assignment for English class, it is far simpler to type in a Web address and use 15 minutes of time to look up a brief synopsis, freeing up the rest of the day to pursue other interests.

The same goes for media like television and movies, which can shrink the plot of a book into a packed hour and a half. With a couple of friends, some snacks and a little free time, one can see the new Jane Eyre movie, even if one detests Victorian-style writing, because the film is made to attract as many people as possible through the use of visual imagery.

Now, the staff of The Feather is not trying to condemn new forms of information; rather, we are seeking to point out some of the flaws these recent media have demonstrated.

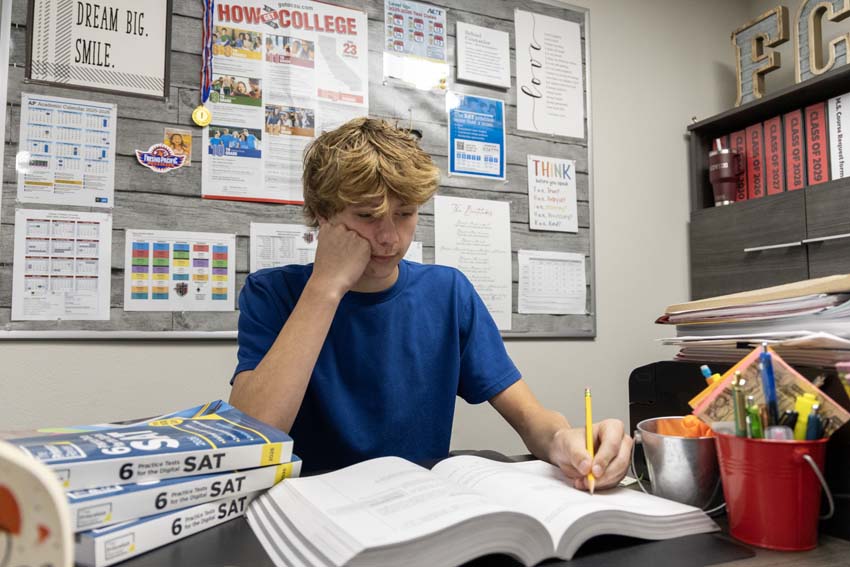

For instance, when people aren’t reading, they are missing out on a major part of the work’s content. It is easy to glance at a TV show or listen to music on iTunes, but to truly understand the inner workings and core of material may take years of practice and study. A skilled reader doesn’t just blindly take in the details in front of him, as it is so easy to do with visual imagery, but he also absorbs as much information as possible from particulars.

This, in turn, affects how well one may do with essays and other language-based areas. If one were to surround oneself with visual influences like TV, one is not likely to do nearly as well as those who surround themselves with novels and narratives, simply because they are two different mindsets. One is relatively simple and fast, while the other is more complex and difficult.

Furthermore, both fiction and nonfiction books can offer the same entertainment value as moving pictures. After all, who could forget the famous detective work of Sherlock Holmes, the magical world of Harry Potter or the examination of humans that many authors have tried to create through books such as Lord of the Flies? On top of those, religious texts, autobiographies and scientific journals attempt to teach society the truths and follies of the past.

Ironically, it is Captain Beatty, the calloused fire chief of Fahrenheit 451 — Ray Bradbury’s sci-fi novel where firemen burn books instead of putting out fires — who sums up what has happened to present-day society: “Speed up your camera. Books cut shorter. Condensations. Digests. Tabloids. Everything boils down to the gag, the snap ending … Classics cut to fit fifteen-minute radio shows, then cut again to fill a two-minute book column, winding up at last as a ten- or twelve-line dictionary resume” (54).

This being the case, we cannot sit idly by and watch the written word slowly dissolve into a lesser and lesser significant enterprise. But how, then, do we attract people to books while there are dozens of different digital media around them? It seems like the only course of action is to remind them that books are indeed interesting.

Everyone has his or her own taste when it comes to music and movies, and books are no different. And, when one does become accustomed to reading, then publications like newspapers and magazines are more tolerable, because one is more used to, and better at, reading. For that reason, The Feather encourages students and adults to retain their reading habits or adopt new ones in the face of increasingly popular electronic media.

For more opinions from The Feather staff, read the February editorial, EDITORIAL: Revamp announcements routine.