Two Important Questions for Those Who Train

This is a blog for students and adults who want to ponder the benefits of exercise, fitness and strength training and their implications for life beyond the momentary endorphin rush or the pursuit of some physical aesthetic ideal. The views and opinions expressed in this blog are founded on several years of personal experience, observation, trial and error (lots of the latter) and study. This is the third of a biweekly series of blogs written by Mick Fuller.

In a previous post I described some of the differences between exercise and training. These differences are important because they answer the question: “What are you doing now?” I also posted that when that question is answered, you find yourself facing two new, more complex questions. The first is about your motivations: “WHY do you train?” The second question is about the process you should use, and it can be posed as either “HOW should you train?” or “WHAT should you DO?” It is necessary to answer these questions if we want to be successful in our physical endeavors. The next few paragraphs will examine the “WHY” question in some detail and begin to explore its connection to the “HOW”.

First, we should know why we train, or at least why we should train. This question addresses our goals and aspirations. There are many reasons for starting a systematic program of training: improved health, increased athletic performance, aesthetic enhancement (for the boys reading this blog, that means “gettin’ swole”, the girls will probably think “toning”, which is a topic for another time) and achieving a sense of well-being are the most common reasons.

Once we identify the specific motivations for beginning to train, we can then articulate goals that will help us organize our training and gauge our success. The overweight man who trains for health might establish targets for blood pressure, weight loss and pre-diabetic markers. The middle aged woman worried about osteoporosis might set goals related to bone density and bmi (body mass index–a general measure of body fat percentage). A high school student may pursue increased power, endurance and muscle mass to be a better athlete. It is important to keep our reasons for training as well as our specific goals in mind so we stay focused and follow through with our plans.

It should be noted that our motivations are usually more complex than a single idea. In fact, many factors, not all of which are overt and conscious, influence our motives. For example, the overweight man described above probably has a medical diagnosis of high blood pressure and his doctor may have even talked about being “pre-diabetic” and said weight loss was an important goal. In this case, the physician’s directive provides the basis for a conscious motivation. However, underlying that may be a less-than-conscious fear of heart disease and premature death, stemming from when the man lost his own father to to a heart attack. Therefore, his motivations for starting to train are both rational and emotional.

In the case of the high school student wanting to be a better athlete, the milieu of factors affecting training motivation is likely just as complex. The student may have aspirations to compete beyond the high school level and knows she must be stronger to impress college recruiters. Basic temperament also plays a significant, albeit subconscious role in her motivations. If she is high in conscientiousness (see explanations of the Big Five Personality Traits) she will be more inclined to diligently pursue strength training as a path to achieving her athletic goals.

If she is also high in agreeableness, a desire to please parents, coaches and others whose approval matters to her, will amplify her motivations to succeed and to use training as a means to that end. Fortunately, as personally significant as the complexity of her motivations might be, it doesn’t have to absorb that much of her conscious energy, once the decision to train has been made and her goals are clear. At that point she can shift her attention to the process of training itself and begin to answer the second big question.

The question of HOW we should train relates directly to the goals we establish. Training is an inherently systematic approach to achieving physical goals. To put it another way, WHAT we DO when we train depends completely on the outcomes we want to achieve in our training. This is where we could get into the specific aspects of exercise/movement selection, intensity, volume, frequency and other factors that make up a training program.

For example, the middle aged woman trying to reverse osteoporosis will require a program that involves weight bearing exercise. This can be most efficiently accomplished with progressively loaded barbell based movements. The specifics of her program will be both universal and unique: universal in that she will apply a general set of movements such as squat, deadlift and bench press that are used by a broad spectrum of trainees, but unique because the intensity, volume, frequency and range of motion will (or at least should) be tailored to her needs and abilities.

To be effective the program must match the goals. In the case of this woman, a program that involves sitting and moving light dumbells with the arms or doing aqua aerobics will not produce sufficient loading of the skeleton to stimulate deposition of new bone material and thus, will not get her to her goals. There are hundreds of books, journal and magazine articles that deal with the subject of programming in much greater detail than is appropriate for this post. I intend to address this topic in some depth in the future with an emphasis on matching up personal goals and programming priorities. And here is a spoiler alert: it will involve barbells! Until then, in whatever you do, strive to be functional.

For the first blog in the series read, Functional Human Blog No.1

For the latest post in the series read, Functional Human Blog No.2 – Exercise

Kyle Friesen • Oct 14, 2018 at 10:49 pm

Getting swole is the ultimate form of strength training. Whenever I forget to ask myself what my goals are, my weights begin to slip this is great advise.

Mick Fuller • Oct 2, 2018 at 2:30 pm

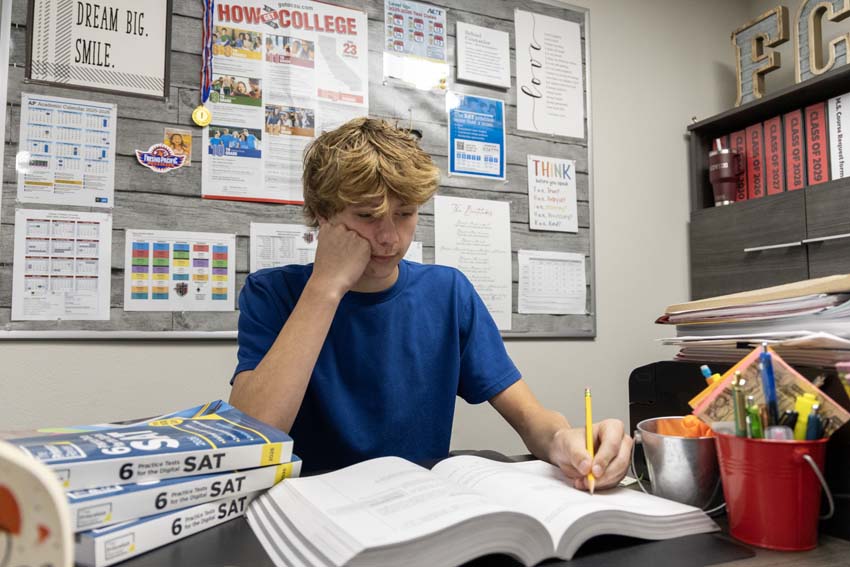

The picture above of the student squatting doesn’t show the precise moment he achieved full depth. A proper squat depth is when the crease of the hip goes below the top of the patella. The picture shows a position about 3 inches above full depth.