In this day and age, immigration has become a rather controversial subject. More specifically though, the undocumented immigrants that are currently living in the U.S. People with different backgrounds and experiences, possess their own opinion on the matter, making the issue at hand a grey area. Due to the embroilment, why not take a step back and look through the eyes of one who has lived through the perplexity itself?

and look through the eyes of one who has lived through the perplexity itself?

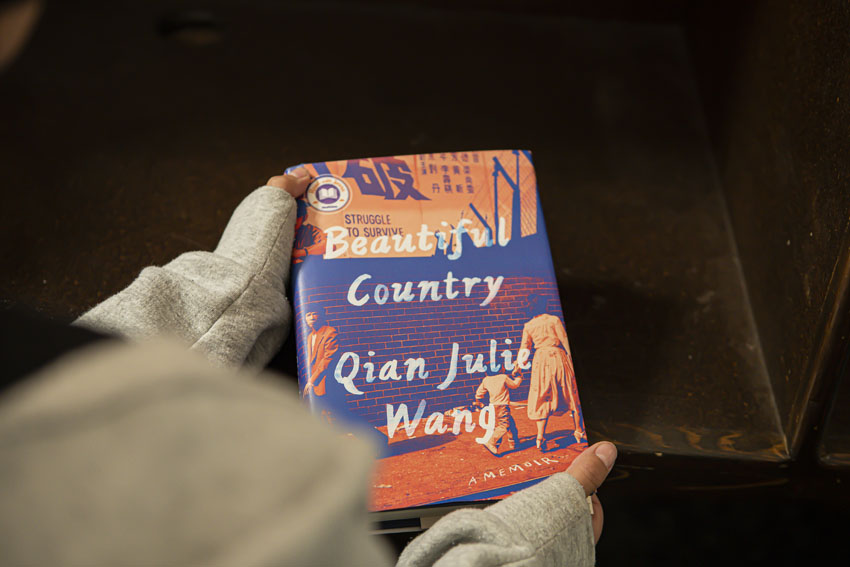

Qian Julie Wang (Chi-en Joo-lee Wong), Yale Law graduate and partner for Gottlieb & Wang LLP, recently released an empowering novel, Beautiful Country, disclosing the adversity of being an undocumented immigrant in the U.S. Wang takes the reader through the first five years of her youth in the U.S. as an undocumented child, providing the reader a picture of life as a Hei, a phrase in Mandarin for the undocumented, literally “to be in the dark.”

The book draws the reader in by conveying raw stories that Wang experienced, bringing a state of despondency because of the heavy material. Yet the emotions of heavy-heartedness just cause interest levels to rise, creating a longing to see how the Wang family will endure through the hardships of living as undocumented immigrants from China.

Wang’s family endured the fear of the tyranny by the Chinese government since her father’s youth. Thus, her parents came to the decision to abscond to Brooklyn, New York — leaving their successful jobs, family and loved ones, as well as their language, behind. Her parents were well-educated and both had plenty of experience being professors; however, when they came to New York, this didn’t seem to matter much. They were once-respected individuals who, to their terror, ended up in sweatshops (and other jobs that employed “minorities”).

Wang immigrated to the U.S. on July 29, 1994 at seven years old. She and her family lived in constant suffering; unfortunately, their living conditions were not nearly suitable for a family of three. They lived in a compact room, residing in a home with other families and having to share a bathroom and a kitchen. A meal was considered a blessing. On a day-to-day basis, racial slurs were being thrown towards the family. At Wang’s young age, she didn’t have the comprehension to even know what the words meant.

On top of everything else, the family faced ceaseless fear of being deported. Wang had been taught to fear the police, the very ones that the everyday people should put their trust in, for they could take her and her parents away. Due to her parent’s paranoia she had been instructed by her father to lie to her school to say that she was born in the U.S.

Centering around the parents and Wang, the novel also includes a variety of minor characters all throughout. Most of the minor characters are included for one chapter, and there may be a possibility of a reference later in the book by Wang. Such as her grandmother, who only said a couple of lines and disappeared, then Wang would recount memories of her grandmother from time to time.

The main issue the family faced was the anxiety caused by the possibility of being deported, the fear may not have been explicitly stated in every chapter but there are underlying hits and factors that were caused because of it, fabricating a tone of dismay.

Coming into the U.S. Wang did not speak or understand any English. When she went to her new elementary school, she was placed in a class specifically for disabled or special-needs children. The teachers alienated her because of the language barrier; despite this, Wang did not become discouraged and instead, filled her time with reading. She read library books and watched PBS, astonishingly teaching herself English.

“Soon, I would make Ma Ma and Ba Ba proud, and it would be just as if I had always been here, as if I had been born here, a native English speaker at last.” -Qian Julie Wang

(Ch. 6 Native Speaker p.g. 73)

Later in her life, a Caucasian man would attempt a few words in Mandarin with horrendous pronunciation. Wang, who was still quite young, called the man out, which earned herself a lecture.

“Why were we expected to speak English perfectly while praising Americans for even the clumsiest dribble of Chinese?” -Qian Julie Wang

(Ch. 13 Mcdonald’s p.g. 134)

Wang’s story is only one example of an immigration tale, people with at least some history correlated to her’s can relate and sympathize. Ones who experienced none of that type of situation can still find some relatability in that everyone undergoes the human conditions: the emotions, the unbreakable familial bond, and the courage to hope.

The novel’s short stories and straightforward writing creates an animated narrative, yet an easy read. Due to the novel moving at such a fast rate one can except to find new pieces of information, each time rereading it.

View this post on Instagram

An indisputable fact is that the undocumented are people too, our brethren. Although the issue at hand is a rather complicated feat, simply overlooking the problem solves nothing.

‘Boiling Frog Syndrome’, based on the urban legend that if a frog is put in lukewarm water and the temperature is slowly being heated up, the frog will simply stay put until their timely demise. The syndrome connects with the topic, by revealing in a rather schematic fashion, many individuals ignore the problem because it does not seem to affect them at the moment, but there will always be a consequence to an action.

At present time, Wang, is writing her second book, unfolding the lives of women of color in the elite law firms. Additionally, she stays involved with her community, and her supporters.

It must be noted that Beautiful Country is based on true events with real people, containing graphic language and imagery that some readers may find disturbing.

AUTHOR Q&A:

What gave you your courage to hope? Time and time again life knocked you down and against all the odds you pushed through; how did you keep the mindset of determination?

I wish for every person two things: (1) a strong and wise mother and (2) access to good books. My mother never failed to remind me, no matter what happened, that things were temporary, and that we would get out of our immediate circumstances. She instilled in me early and often a sense of agency, and a conviction that I would be able to find my way out of poverty and deprivation. Further, the books I discovered in the public library—my first place of refuge in America—gave me the insight that even though I was living under different immediate conditions, worries, and labels, my dreams, hopes, and wishes were not so different from those of the next American kid.

What was going through your head when you finally became a U.S. citizen?

Walking to my naturalization ceremony in May 2016, 22 years after I first stepped foot at JFK Airport in 1994 was a torrent of every imaginable emotion. First, it felt like an actual torrent because as I stepped out of my law office in downtown Manhattan to walk the few short blocks to the courthouse for the ceremony, the weather changed from clear skies to pouring rain. I did not have an umbrella, and remember looking up at the sky and muttering, “Really? You’re really going to make it hard for me until the very last second?!” I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Second, when I, drenched in rainwater, finally entered the room for the swear-in ceremony, I felt another wave—this time of joy, peace, anger, nostalgia, and disbelief. When, via a video screen, President Obama greeted me and everyone else in the room as “fellow Americans,” something in me came unglued. I realized then for the very first time how badly I had needed to be called American for so much of my life, and how nobody would ever ascribe that term to me. From then on, and particularly going into the 2016 election, something fundamentally shifted within me. I have never failed to lose that newfound sense of privilege, power, and responsibility—the ability and choice to finally speak up about my experiences because there are still so many millions who do not have that luxury.

How does it feel to not only inspire immigrants and undocumented people from China but also from Mexico and many others who are going through a similar situation?

I do not think of myself as being inspiring. Indeed, I am inspired every day by immigrants of all origins whom I am lucky to know. And I never could have dared to share my story without the inspiring courage of Jose Antonio Vargas and Karla Cornejo Villavicencio.

What I am, really, is privileged. I am privileged in that I was only undocumented for a finite number of years. I am privileged because I had loving, educated parents who instilled in me a sense of agency and empowerment, and the conviction that literacy and narrative was my way out. I am privileged to still have my law degree and experience. I therefore believe that I am simply living up to my immense privilege and carrying out my duty to speak up because I have the unique ability to do so, when so many others do not know when, if ever, they can hope to be recognized under law as the productive and patriotic Americans they are.

I also want to make clear that I cannot possibly speak for all immigrants. Each immigrant, and each undocumented immigrant, has a unique story of how and why she came to live in and love America. By writing and sharing my story, I only hope to shed light on the humanity and the beating heart behind the headlines, and to erode the stigma so commonly inflicted upon the courageous and inspiring undocumented Americans who are such vital members of our communities.

[rwp_box id=”0″]

For read more Feather book reviews go to The Ride of a Lifetime

For more Feather articles Go to Rachel Moate builds business amongst high school pressures.

Tony • Nov 5, 2021 at 9:07 am

This article truly sheds some light on a topic that should not be as controversial as it is, or can be at times. It sheds light on the modern day immigrant, and the trails that we have faced, regardless of race.

Silva Emerian • Oct 29, 2021 at 10:05 am

Way to go, Emma! Amazing article – well done!

Lizzy • Oct 28, 2021 at 2:02 pm

So good Emma!!!